From the MCRFB news archive: 1970

From the MCRFB news archive: 1970

Mercury Records Under Fire for Pandering Music Many in Radio Regard Obscenity

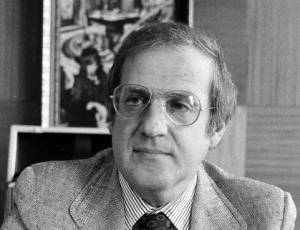

CHICAGO — Mercury Records President Irwin H. Steinberg told broadcasters gathered here that it is their responsibility to determine if recordings are obscene. A music director countered saying such an attitude was “presumptuous” but Steinberg never backed down.

Moreover, the record company executive told the National Association of Broadcasters meeting that it would be “awful” if repressive measures inhibit labels from remaining conduits for the feelings (expressed) of young people, black people, and all kinds of other people.

During a hard-hitting session touching on nearly all of radio station record programming except “the distribution problem,” Steinberg talked openly about Mercury’s problem with the sexy French hit. “Je T’ Amie… Moi Non Plus” which sold 150,000 copies without not much airplay.

Mercury has drawn fire from broadcasters for recordings involving drug messages and profanity, he admitted. Veteran Georgia broadcaster and legislator, Edwin Mullinax, recently lashed out at the label for the use of “hell” and “goddamn” in a single.

Differences

Referring to complaints from broadcasters, Steinberg said: “There are amazing different attitude towards product. I had calls from two broadcasters 100 miles apart. One wanted to know how he could obtain six more copies of ‘J Te Amie…’ and the other stated that he and I really make the determination as to what people heard — had to set standards as to what morality was supposed to be.”

Steinberg said it is his opinion that there is really no way defining ‘obscenity.’ He said: “First, I will say obscenity is a highly emotional thing. There is no way measuring it objectively.”

“I will differ with you in terms of education, family, background, ethnicity, you name it — all kinds of area of exposure — and come to a different conclusion and so will you.”

“We have our measurement of what is obscene and it’s probably close to what the pornography report recently turned out by the President’s commission, which unfortunately, I think, he rejected.”

Steinberg hesitated as he went one step further to define obscenity. “The best word I can think of is disgusting — but we can get into a hell of an argument about what’s disgusting to.”

He said that he expected stations to listen to his product and that since a “hell of a lot of it is rejected” that stations must be listening.

“As far as I am concerned, we have a management responsibility to turn out product that sells and I must tell you that I don’t stand on that alone. I have some personal pride in the kind of product we turn out as well.”

A Conduit

He said that his company felt to a certain extent what it turns out mirrors what is happening in America today — or throughout the world in the case of international product — and added: We’re sort of proud to be a conduit to a great extent for the feelings of young people, black people, people of all kinds. We feel we are such a conduit and I think there are not enough people who understand that.”

When it comes to lyric messages of love, drugs, obscenity and nonsense songs, he said: “It’s your job as far as I’m concerned to listen and decide whether you accept it or reject it; whether you feel it’s good or bad for your audience. We’re going to have to face either the success of the product or its consequences”

Later, during questions and answers, when his position and that of other labels was called presumptuous, Steinberg said that stations did not have to accept whatever was his own personal standards or those of his company — “I haven’t said that. You have a right to listen and reject just as your listener can switch to another station on the dial.”

Repression

He reiterated in saying “repressive” measures would be an “awful” mistake and added: “I hope we don’t get the kind of repressive measures that limit this kind of mirroring of what’s going on in our society.”

He equated this possibility to the “great blues we had in the past years that reflected the kind of anguish that the blacks felt during our greatest years of slavery.

In those times I’m sure there were a hell of a lot of people who would have preferred that whatever communications the blacks had about their problems didn’t exist. And I think that on the same basis it would be a mistake not to provide this conduit for the feelings of young America.

I think you’re in a hell of a spot to give an opportunity to the public to accept or reject the kind of poetry that young people are expressing.” END

(Information and news source: Billboard; November 7, 1970).

![]()