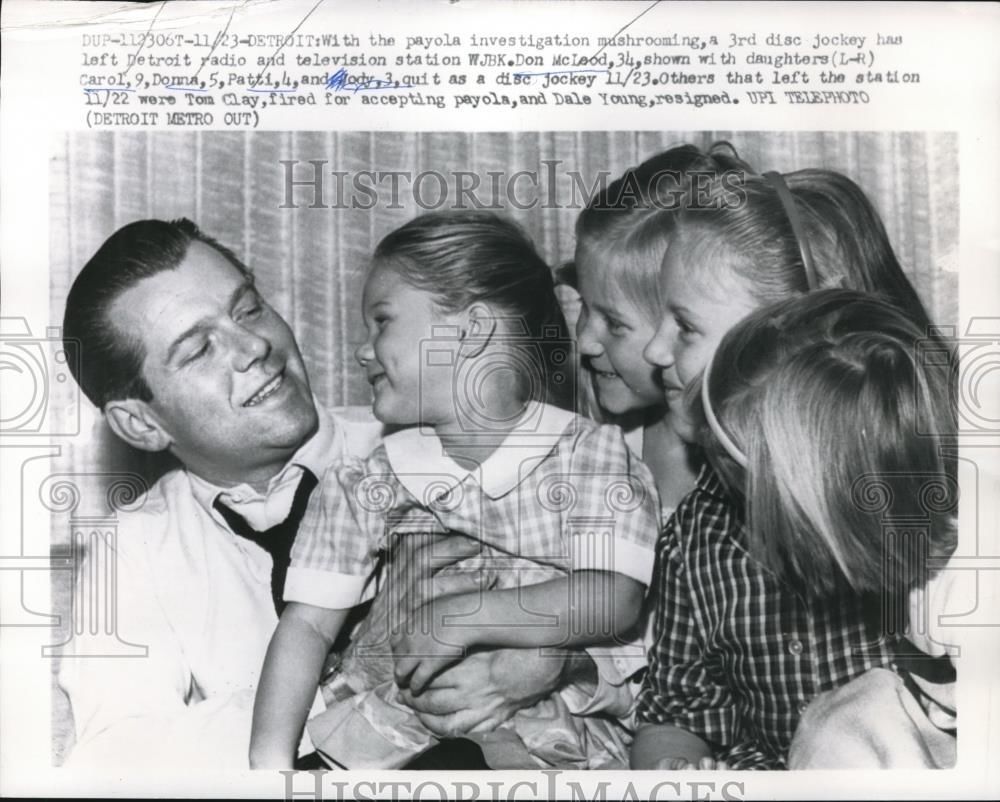

From the MCRFB news archives: 1959

From the MCRFB news archives: 1959

LIFE MAGAZINE (November 23, 1959)

” . . . . clear evidence of disk jockey bribery crops up.”

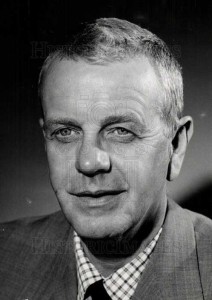

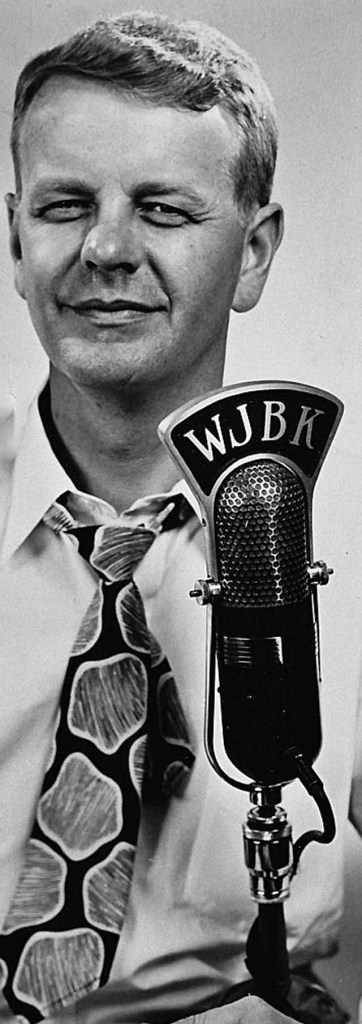

Edmond T. McKenzie, has worked in broadcasting in Detroit since 1937. His career, income and popularity had gone steadily upward until he quit bigtime radio in disgust some eight months ago. Here he tells what made him want to leave.

By ED MCKENZIE

Eight months ago I quit a $60,000-a-year disk jockey job on Detroit radio station WXYZ. I could not stand present-day “formula radio” (See MCRFB: ‘Veteran DJ Ed McKenzie Quits On WXYZ’ March 16, 1959) — its bad music, its incessant commercials in bad taste, its subservient to ratings and its pressure of payola. Because of the charts that are put together by numbers of music trade publications (Billboard; Cashbox) that rate the popularity of records, I had to play music on my program that I would never have played otherwise. And the charts are phony because of the most disgusting part of the radio industry — payola.

Payola really got started about 10 years ago. Until then the record business was controlled by the big companies by Decca, Columbia, RCA-Victor and Capitol. When the obscure little record companies started up and begin turning out offbeat records by unknown artists, they looked for a way to get their product distributed and played. The answer was payola: offering disk jockeys cash to play records they wouldn’t ordinarily play.

I never took payola because it was completely dishonest, but I was often approached by small companies who were having a tough time getting their stuff on the air. They would say, “Well, how much do you want to ride this record for the next three weeks?” They might offer $100 for a one week ride, which would have meant playing the record several times a day to make it popular.

Many disk jockeys are on the weekly payroll of five to ten record companies, which can mean a side income of $25,000 to $50,000 a year. The payment is by cash in an envelope. Phil Chess, co-owner of Chess, Checker and Argo Records, told me that when he called on certain disk jockeys to promote his records, the first question some jocks would ask was, “How many dead presidents are there for me?” Dead presidents means the president on bills. A $20 bill is a “Jackson.”

The small companies know that if it can score in a key record-selling city — Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland or Pittsburgh — it will score nationally. If an unknown artist on an obscure label makes some noise in one of these cities, the record sales are promptly published in the trade papers — Billboard, Cashbox, Variety. Other jockeys around the country sees these listings, and a chain-reaction is set off. The offbeat record becomes a money-making hit, all through payola.

Another way to rig the key cities is to fix the bestseller charts. I know many record production men who takes out a girl who works on the local chart. They give her a big time, wine her and dine her, buy her gifts, become very friendly. Then they get her to list their record, even if it isn’t a best seller.

It’s even worse in the big-time. Many music publishers tell me that to get a song played on one popular teenage program, they have to give the star 50% of the song. He wants either half the song or a half-interest in the recording artist before he will put it on his program. He rejects many songs because he can’t get a piece of the record.

“Slicing up an artist” in this way oftens involve a jockey. A few years ago we had a case like this in Detroit when a New York song plugger, a nightclub owner and a local disk jockey sliced up Johnny Ray early in his career. They pushed and plugged him in Detroit until he became popular, but they never got their cut of Ray subsequent bug earnings. Johnny Ray didn’t dare come back to sing in Detroit until he bought back the club owner’s share of his contract.

Payola usually begins when a song plugger or publisher comes to town and takes the jockey out for dinner. The sky’s the limit on entertainment — drinks, girls, everything. There is always a big follow-up at Christmas. They flood you with liquor, TV sets, hi-fi sets, expensive luggage, big baskets of food, expensive watches, silk shirts, imported sweaters. The flow doesn’t stop after the holiday season. A record plugger once offered to install a bar in my basement. When one Detroit jock moved into a new home, his property was landscaped with hundreds of dollars worth evergreens and flowering shrubs and trees.

Once when I had tried to squelch a song plugger who was after me to play a certain tune, he mailed me a $100 government bond in my name. I was the only person who could cash it. I did cash it for $75, added $25 of my own in interest and mailed a $100 check to Leader Dog for the Blind. I mailed the donation receipt to the song plugger and said, “This is where your money went.” I never played his record.

Radio station managers are aware of all the bad practices of payola, but I guess they take the attitude that “the kid isn’t making much salary here, so if he can make a little on the side, God bless him.”

Bad as payola is, it isn’t the only thing an honest disk jockey has to fight. Between each record you are required to give two, three or four commercials. Even though I was paid a commission for each commercial I gave at WXYZ it bothered my conscience terribly. I knew that I was driving any intelligent listener away from radio with this drivel.

How could anyone bear to listen to this sort of thing? One answer was given by Leonard Goldenson, president of American Broadcasting-Paramount Theaters. He said the ABC network was after one listener, the housewife just out of her teens. That is why you hear this so-called teenaged rock ‘n’ roll junk.

All of this — payola, ratings, the bad ratings, the obnoxious commercials — was far more than I could take, so last spring I quit formula radio. I have since joined a group of other radio mavericks at WQTE, a small daytime station station between Detroit – Monroe. On this station I feel like I can honestly entertain people without the excessive commercialism, and I don’t have to play any music unless I think it’s good. The station is only 500 watts — but it’s honest. END

(Information and news source: LIFE; November 23, 1959).

![]()